UK Mortgage Mayhem: are we becoming a “developing” country?

I am among the 13% of mortgage owners who are due to remortgage this year at the peak of the rate hiking cycle. Since 20% of homeowners have already refixed at the start of the hiking cycle, it leaves a good chunk of people to do so over the next few years.

UK housing were already extremely unaffordable. And most households were paying a high portion of their salary towards mortgages (also rents). We have one of the highest inflation rates within the developed world, and now even competing to look “better” against developing countries where inflation has fallen back down very quickly. To make the cost-of-living crisis worse, mortgage rates have started to hit the roof. High interest rates are hardly getting passed on to savers. And even if they did, do most of us have anything left over to even save?

In this post I demystify what is REALLY going on in the UK mortgage market and what we can do about it.

The United Kingdom: now a “developing” country?

I’ve recently come across a FT article written by the president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, Adam Posen. He argues that it is time for the UK to think like an emerging market. In other words, policymakers should now act as though they are under a self-imposed IMF stabilisation programme.

So, is the UK really starting to look like a developing country? It’s not a new question, but one that’s been asked multiple times since the flatlining of productivity growth from the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. Productivity is key to a country’s overall growth, and it shows how much output we are generating per unit of input used. A stable growth rate has a strong bearing on the housing market, interest rates and affordability.

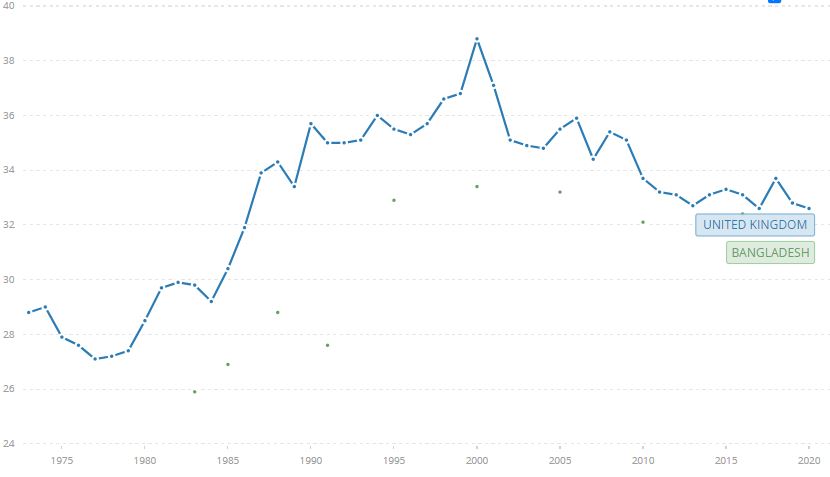

Outside of economic growth, not only we’ve gone the other way when to comes to wealth inequality, we are also further behind from Nicaragua and are struggling to keep up with Serbia with respect to gender equality (WEF 2021 gender equality ranking). UK’s recent Gini coefficient (a measure of wealth inequality) as calculated by the World Bank is in line with Bangladesh’s score back in 2016 (chart below).

And, at the time of writing UK’s inflation rate stands at 8.7% (May 2023), compared to 3.0% in the US, 3.2% in Brazil, 4.8% in India and 6.3% in South Africa. Yes, that is right! Our inflation is much higher compared to ’emerging market’ economies, which, by nature, are expected to have higher inflation rates.

UK housing: Most unaffordable in c.150 years

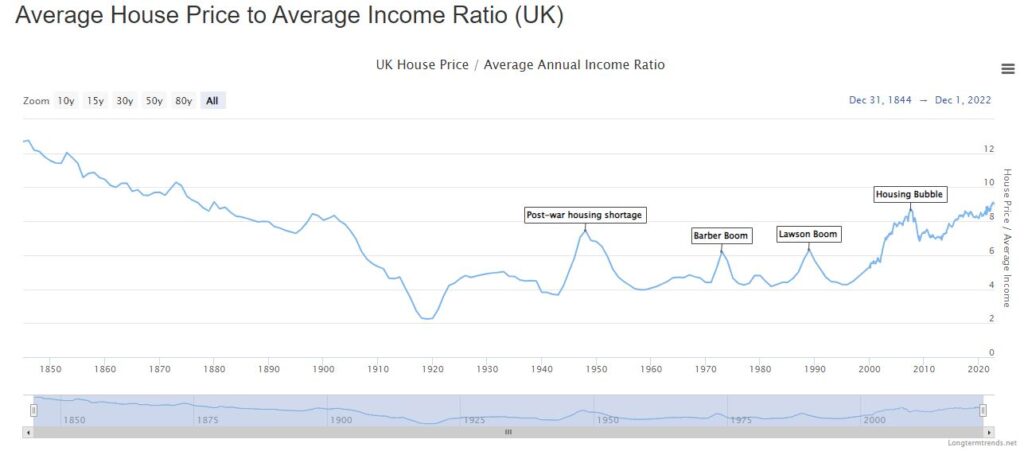

Whether nationals of a country can afford to buy a house to live in is also a measure of how “developed” and “wealthy” that country is. Without quoting any numbers, if you live in the UK, particularly in London – you will “know” where we stand on affordability. It’s steep. Last time UK homes were this much unaffordable was back in the Victorian era, in 1876.

In 2023 UK, an average single earner household makes around £32K and the average house price is 9x of that amount. In the US, it is x4. Even mortgage cost as percentage of income is staggeringly high here, despite the historically low interest rate. This suggests how weak our wage growth has been. Data from Numbeo show that mortgage cost as % of take-home income is c.66% compared to 38% in the US.

Against this backdrop, as mortgage rates begins to pick up now it will only exacerbate the current situation.

Mortgage rates: hitting the roof

Broadly speaking, we have two types of mortgage rate type to choose from: variable and fixed.

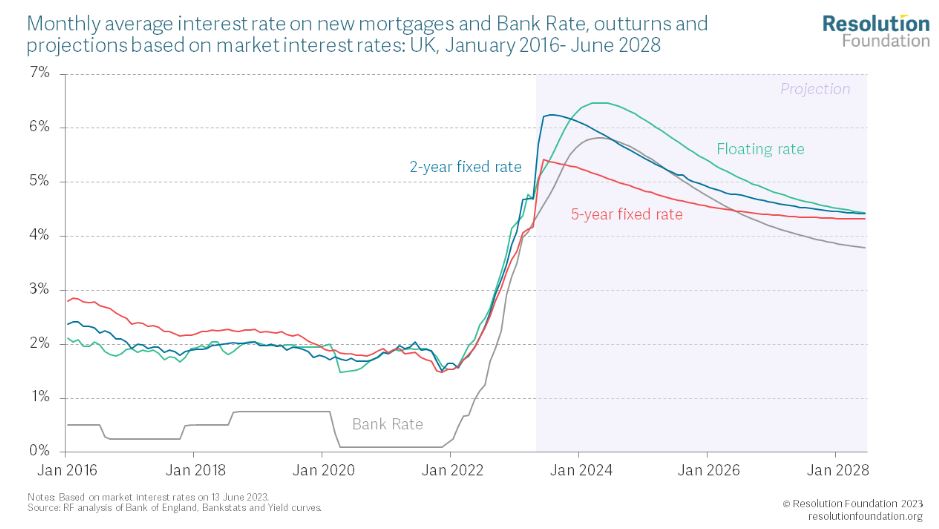

Variable rate mortgages are linked to the current interest rates set by the Bank of England. Therefore, it rises with rate hikes and falls with a rate cut. In contrast, fixed rate mortgages typically follow the government bond market which relies on the future path of those interest rates set by the Bank of England. Mortgage providers would look at what would likely be interest rates in 2 to 10 years in order to set their own rates. This is very much market driven.

Generally, longer the fix, expensive it is as you are guaranteeing repayment costs to remain the same for a longer period of time which is a risk to the mortgage provider should rates increase higher over the duration of your mortgage term. However, what I have noticed lately is that 2 years rates are now significantly higher than the 5-year rate. This highlights the fact that the market thinks rates will fall lower over the 5 years, so mortgage providers are happy to drop the rates for that. In contrast, over two years it is expected to remain higher or go even higher which increases uncertainty for the banks and hence they are charging higher rates for a short-term fix. At the time of writing, 2y fix is going at 6.7% vs 4.8% for a 5y.

UK economy: What's the impact?

From a macroeconomic perspective, various analysis suggest that the impact will be less severe than the last mortgage crisis of the 90s when mortgage rate hit 13%. However, it will not go unnoticed. There are a couple of reasons behind why it will not be as severe at an aggregate level:

Decline in number of people owning mortgages.

Only 30% of households own a mortgage now. This means direct cost of higher mortgage rates will only impact a small percentage of UK households. This is driven by more older people owning their homes outright and less young people being able to afford it at all. Despite this, there are reasons to worry because it seems that the higher rates are fast to impact the rental market than the mortgage market (also noted at the June BoE MPC meeting minutes). And if more people are now renting, a higher cost of rent would make the cost-of-living crisis worse.

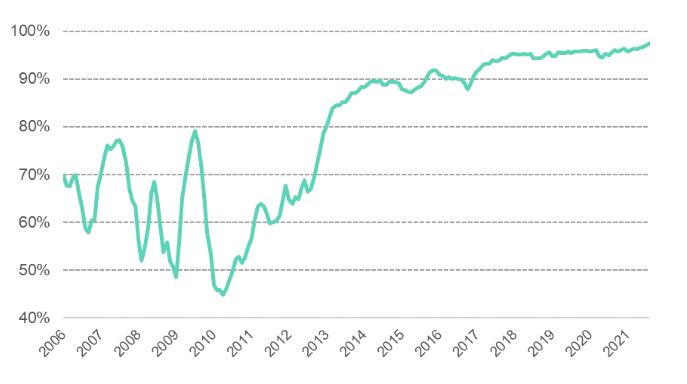

There are now more fixed rate mortgages in the economy compared to variable rate.

In 2012, fixed rate mortgages made up only 30% of all mortgages compared to nearly 90% now. So, the rate hikes wont be hitting most people all at once.

More higher duration fixed rate mortgages

Within fixed-rate mortgages, higher duration product like 5 years instead of 2 years have become more popular. This means impact from rate hikes are likely to take effect more slowly.

The “extra” savings people made during the pandemic – offering some buffer.

Data from ONS show that UK households have started to dip into those savings either to pay for the increased cost of living or to pay off the mortgage early. In May, UK households reached a record when £4.6bn more money was withdrawn than deposited. This was the highest net withdrawal since the record began 26 years ago.

UK national: What's does it mean for you?

Since I don’t know you personally, my readings from ONS suggest that those who are refixing this year, (that includes me) would have been paying an average 2.5% rate on their mortgage. FYI, mine was fixed at 2.3% in 2018. However, the average rates on new loans are currently 5%. This suggest that the full pain of higher mortgage rate has not come through yet. When that gap narrows, it would.

Example:

Let’s assume you have a £200K mortgage to be fixed for 25 years. When you remortgage now at 6%, instead of 2.5%, your monthly cost would be jumping from £900 to £1300, a 44% increase.

Let us also assume, you are on £32K salary which makes your net home pay after tax and NI (assuming no contribution to pension) to be £2,318.

Rule of thumb is to keep mortgage payments below 35% of take-home pay. Generally, lenders use 28% on your gross salary when making mortgage offers. In our example, we are already hitting above the 35% best-practice target. Before the increase in rates, 39% of the net pay would’ve gone towards mortgage, and this number jumps to 56% when rates increase to 6%.

This tells me that whilst on aggregate, the current mortgage crunch will be slow to impact the UK economy, everyone’s experiences will be very different. Single earning households will be particularly vulnerable.

I think, renters would struggle a lot more too because buy-to-let mortgage rates tend to be more expensive than the residential ones. Renters also generally have low savings, and it will appear that the landlords would be quick to pass on those higher cost to their renters.

Whilst the higher interest rate will surely stop people from spending, it will hurt the middle to low-income households the most. This is because even though high interest rates are expected to encourage saving, the even higher cost-of-living would mean there will be nothing left to save. Therefore, it will be left only for the wealthy household to save more at higher rates, making the rich richer.

You: 5 things YOU can do

This mortgage crunch will be extremely painful for those who are directly impacted. Here’s my 5 personal suggestions:

- If remortgage is due now, it might be worth trying to fix at interest only mortgage instead of a full repayment (if possible). This means you will not be lowering the amount borrowed, instead only pay the interest on the loan. However, the risk with this option is that if you are already at a higher Loan-to-Value (LTV) mortgage and if house prices fall, when it comes to remortgaging later you may hit a higher LTV ratio, increasing your cost of borrowing again.

- You may also consider extending the mortgage duration as much as possible. For example, I initially took out a 40y mortgage and so I would now be looking at a 35-year mortgage. However, given my ag, my broker mentioned that I could extend it out to 37 years. Doing so is reducing my monthly cost. If you look to do something similar, do note that it will increase the overall cost you pay during the mortgage term (i.e., 37 years for me). However, this can be counteracted by overpaying as and well you are able to. I have been overpaying my mortgage over the past few years. I liked the flexibility without the commitment.

- If remortgage is due within the next 12-18 months, start to build up buffer by saving more in those high interest accounts. Simple calculations can show how much extra you’d need to pay when on a high rate. It will be a good idea to start saving those extra from now to get used to the new budget and also build buffer.

- Rent out a spare room. This will not only help those who are struggling to find a rental properly (especially in London), it can also pay significantly towards the monthly cost. A typical double bedroom in London can earn between £400 to £1000. If long-term rental is not your thing, you can consider renting out on Airbnb as and when you feel the need.

- Pause investing in risky parts of the market like the stock market. I know, investing is really important, but it does not form part of our basic needs. Given the choppy market movements, it won’t be a bad idea to redirect investing towards your contractual payments such as mortgage instead of dipping into savings.

Tell me more about experience. You can find me on Instagram under @TheSubtleInvestor